共计941条影片

天狗党

HD

1864年(元治元年),德川幕府岌岌可危,国内各藩蠢蠢欲动,国外列强叩响国门。是年,水戸藩士藤田小四郎等下级武士以“尊王攘夷”为口号,组建天狗党,在筑波山起兵。一时间,保守派和激进派纷争不断,狼烟四起,整个国家陷入动荡之中。

底层农民真壁仙太郎(仲代达矢 饰)因拖欠地租被地主鞭笞,为路过的天狗党头目新五左卫门救下。备受感动的仙太郎决心加入天狗党,革新时弊,扫除压迫。然而一次次的行动,让他对天狗党的作为和宗旨渐渐产生怀疑……

红星照耀中国2019

HD

《红星照耀中国》电影剧组创作灵感及素材就取自同名报告文学——美国记者斯诺根据自身经历创作的《红星照耀中国》一书。影片主要讲述的是1936年美国青年埃德加·斯诺冒险来到中国红色革命区域的的亲历见闻,在采访和见证了毛泽东、周恩来等共产党领导人,以及红军战士和苏区百姓的风采之后,斯诺以饱含激情的生动文笔写成了《红星照耀中国》一书,该书出版后轰动世界,使全球第一次了解到了彼时艰苦抗战背景下中国共产党的真实情况。

打过长江去

HD

《打过长江去》以渡江战役为背景,再现了新中国成立前的关键时刻,人民解放军一支先遣分队潜入江南,打进虎穴斗智斗勇,命悬一线却与各种敌人殊死斗争,为祖国统一而舍生取义、无私拼搏, 最终配合百万大军过长江,将红旗插遍中国。

小戏骨:洪湖赤卫队

HD

小戏骨《洪湖赤卫队》是以王玉珍主演的《洪湖赤卫队》为蓝本改编,讲述1930年湖北沔阳县委为配合红军行动,暂时把赤卫队撤离彭家墩。彭家墩恶霸彭霸天趁红军转移暂离洪湖之际卷土重来。洪湖赤卫队在乡党支部书记韩英和队长刘闯的带领下,与敌人展开了艰苦曲折的斗争。韩英不幸被捕入狱。面对敌人的威逼利诱,韩英始终坚贞不屈。赤卫队最终打回彭家墩,消灭了保安团和地方反动武装,红旗又在洪湖上迎风飘扬。

解放·终局营救

HD

1949年1月,中国人民解放军将国民党 50 万军队围困于平津地区,总攻在即。是否能和平解放北平,取决于天津一战。此时的天津城内,暗堡、工事林立,士兵荷枪实弹进入状态,大战前的天津城已是一座炼狱。为了总攻的发动扫平道路,解放军炮兵侦察连连长蔡兴福、侦察兵马宝树、报务员廖枫、炮兵见习参谋葛贵忱四人临危受命,组成解放炮兵侦察别动队,乔装潜入天津城。此时,负责转移北平守军眷属的国军军需官姚哲在宪兵营长钱卓群的暗算下成为通缉犯,带女儿出逃时恰好与进城的蔡兴福一行人相遇,蔡兴福挟持姚哲欲完成任务。随着目标任务的逐步明晰,姚哲被暗算背后的秘密、钱卓群企图破坏北平和谈的阴谋、蔡兴福失踪儿子的下落都渐渐浮现出来……

八子

HD

上世纪30年代的赣南地区,在这个被称为中国革命“红色摇篮”的地方,曾经有这样一位母亲,她将八个儿子先后送入红军,奔赴战场前线。但战火无情,兄弟中的六人陆续牺牲,只剩下大哥杨大牛和最小的孩子满崽。满崽找到了大牛的部队,成了哥哥麾下的普通一兵,一场场艰苦战役的淬炼让新兵满崽迅速成长为一个真正的战士。最后的战斗打响了,为了掩护大部队安全撤离,杨大牛带领弟弟满崽和全体战友浴血肉搏,直至弹尽粮绝……

英雄的身前,是枪林弹雨的沙场,而在英雄的身后,家乡的村庄依然宁静安详,微风吹过金黄的稻浪簌簌作响,一位年迈的母亲正在村头的小路旁孤独的守望……

影片根据江西赣南地区家喻户晓的“八子参军”的故事改编。在战火硝烟的年代,千万人民群众投入到支援革命战争中,奉献了自己的一切。作为那个残酷年代的缩影,骨肉相连的母子情、不离不弃的兄弟情、赤胆忠心的家国情.....无数荡气回肠、难以割舍的情感凝聚于影片之中,共同谱写了一首可歌可泣、永垂不朽的英雄乐章。

法尔什家族

HD

夜幕降临,一架四引擎飞机在机场着陆,走下飞机的是唯一的乘客乔•法尔什——作为法尔什犹太家族最后的幸存者,自从他1938年离开柏林,至今已有四十个年头。在机场到达大厅里等待着乔的,是包括父母、姐妹、兄弟等在集中营丧命的死去的家族以及乔之前所深爱、最终在柏林的轰炸中丧命的纳粹分子的女儿莉莉。一场跨越生死世界的庆典与邂逅就此展开。本片是比利时著名导演组合达内兄弟的剧情片处女作。(小易甫字幕组)

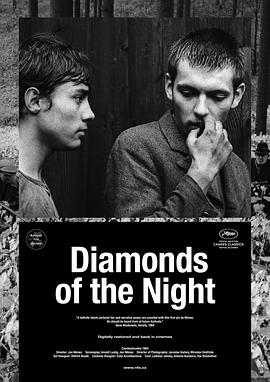

夜之钻

HD

杨·南曼奇在捷克新浪潮的地位,类似于雷奈在法国新浪潮一样。这是他的第一部剧情长片,描绘两个犹太男孩在被送往死亡集中营的途中,从火车上逃脱,被迫在乡野展开挣扎,艰难地求生存的故事,看似具备写实的基础,却被混合了幻想的影像,以及自由跳跃的叙事所重组。

中国蓝盔

HD

我国首部维和军事题材电影《中国蓝盔》讲述了当下中国维和部队官兵在非洲坚决执行习主席指示的“构建人类命运共同体”的大国方针、严格履行联合国赋予的使命,派出了以“兵王”杜峰为首的作战小组冒着生命危险,从恐怖分子手中救出联合国调查组,从而阻止了一场一触即发的战争,维护了难民营的生活秩序、保障了难民们的生活权益。但是年轻的战士也在这次行动中为了维护非洲的和平而献出了宝贵的生命……

无问西东

HD

如果提前了解了你所要面对的人生,你是否还会有勇气前来?吴岭澜、沈光耀、王敏佳、陈鹏、张果果,几个年轻人满怀诸多渴望,在四个非同凡响的时空中一路前行。

吴岭澜(陈楚生 饰),出发时意气风发,却很快在途中迷失了方向。沈光耀(王力宏 饰),自愿参与了最残酷的战争,他一直在努力去做那些令他害怕,但重要的事。王敏佳(章子怡 饰)最初的错误,只是为了虚荣撒了一个小谎;最初的烦恼,只是在两个优秀的男人中选择一个。但命运,却把她拖入被众人唾骂的深渊。陈鹏(黄晓明 饰)把爱情摆在了理想前面,但爱情却没有把他摆在前面。他说,“我有人要照顾”,纵然这意味着与所有人作对,意味着要和她一起被放逐千里。张果果(张震 饰),身处尔虞我诈的职场,“赢”是他的习惯。为了赢,他总是见招拆招,先发制人。而有一天,他却面临了一个比“赢”更重要的选择。这几个年轻人,在最好的年纪迎来了最残酷的考验,并成就了永不褪色的青春传奇。

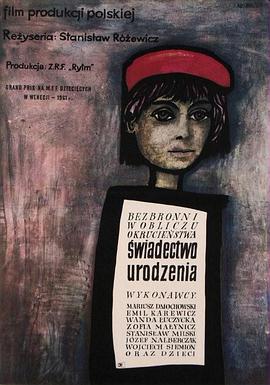

出生证明

HD

In 1961, Stanislaw Rozewicz created the novella film "Birth Certificate" in cooperation with his brother, Taduesz Rozewicz as screenwriter. Such brother tandems are rare in the history of film but aside from family ties, Stanislaw (born in 1924) and Taduesz (born in 1921) were mutually bound by their love for the cinema. They were born and grew up in Radomsk, a small town which had "its madmen and its saints" and most importanly, the "Kinema" cinema, as Stanislaw recalls: for him cinema is "heaven, the whole world, enchantment". Tadeusz says he considers cinema both a charming market stall and a mysterious temple. "All this savage land has always attracted and fascinated me," he says. "I am devoured by cinema and I devour cinema; I'm a cinema eater." But Taduesz Rozewicz, an eminent writer, admits this unique form of cooperation was a problem to him: "It is the presence of the other person not only in the process of writing, but at its very core, which is inserperable for me from absolute solitude." Some scenes the brothers wrote together; others were created by the writer himself, following discussions with the director. But from the perspective of time, it is "Birth Certificate", rather than "Echo" or "The Wicked Gate", that Taduesz describes as his most intimate film. This is understandable. The tradgey from September 1939 in Poland was for the Rozewicz brothers their personal "birth certificate". When working on the film, the director said "This time it is all about shaking off, getting rid of the psychological burden which the war was for all of us. ... Cooperation with my brother was in this case easier, as we share many war memories. We wanted to show to adult viewers a picture of war as seen by a child. ... In reality, it is the adults who created the real world of massacres. Children beheld the horrors coming back to life, exhumed from underneath the ground, overwhelming the earth."

The principle of composition of "Birth Certificate" is not obvious. When watching a novella film, we tend to think in terms of traditional theatre. We expect that a miniature story will finish with a sharp point; the three film novellas in Rozewicz's work lack this feature. We do not know what will be happen to the boy making his alone through the forest towards the end of "On the Road". We do not know whether in "Letter from the Camp", the help offered by the small heroes to a Soviet prisoner will rescue him from the unknown fate of his compatriots. The fate of the Jewish girl from "Drop of Blood" is also unclear. Will she keep her new impersonation as "Marysia Malinowska"? Or will the Nazis make her into a representative of the "Nordic race"? Those questions were asked by the director for a reason. He preceived war as chaos and perdition, and not as linear history that could be reflected in a plot. Although "Birth Certificate" is saturated with moral content, it does not aim to be a morality play. But with the immense pressure of reality, no varient of fate should be excluded. This approached can be compared wth Krzysztof Kieslowski's "Blind Chance" 25 years later, which pictured dramatic choices of a different era.

The film novella "On the Road" has a very sparing plot, but it drew special attention of the reviewers. The ominating overtone of the war films created by the Polish Film School at that time should be kept in mind. Mainly owing to Wajda, those films dealt with romantic heritage. They were permeated with pathos, bitterness, and irony. Rozewicz is an extraordinary artist. When narrating a story about a boy lost in a war zone, carrying some documents from the regiment office as if they were a treasure, the narrator in "On the Road" discovers rough prose where one should find poetry. And suddenly, the irrational touches this rather tame world. The boy, who until that moment resembled a Polish version of the Good Soldier Schweik, sets off, like Don Quixote, for his first and last battle. A critic described it as "an absurd gesture and someone else could surely use it to criticise the Polish style of dying. ... But the Rozewicz brothers do no accuse: they only compose an elegy for the picturesque peasant-soldier, probably the most important veteran of the Polish war of 1939-1945." "Birth Certificate" is not a lofty statement about national imponderabilia. The film reveals a plebeian perspective which Aleksander Jackieqicz once contrasted with those "lyrical lamentations" inherent in the Kordian tradition. However, a historical overview of Rozewicz's work shows that the distinctive style does not signify a fundamental difference in illustrating the Polish September. Just as the memorable scene from Wajda's "Lotna" was in fact an expression of desperation and distress, the same emotions permeate the final scene of "Birth Certificate". These are not ideological concepts, though once described as such and fervently debated, but rather psychological creations. In this specific case, observes Witold Zalewski, it is not about manifesting knightly pride, but about a gesture of a simple man who does not agree to be enslaved.

The novella "Drop of Blood" is, with Aleksander Ford's "Border Street", one of the first narrations of the fate of the Polish Jews during the Nazi occupation. The story about a girl literally looking for her place on earth has a dramatic dimension. Especially in the age of today's journalistic disputes, often manipulative, lacking in empathy and imbued with bad will, Rozewicz's story from the past shocks with its authenticity. The small herione of the story is the only one who survives a German raid on her family home. Physical survial does not, however, mean a return to normality. Her frightened departure from the rubbish dump that was her hideout lead her to a ruined apartment. Her walk around it is painful because still fresh signs of life are mixed with evidence of annihilation. Help is needed, but Mirka does not know anyone in the outside world. Her subsequent attempts express the state of the fugitive's spirits - from hope and faith, moving to doubt, a sense of oppression, and thickening fear, and finally to despair.

At the same time, the Jewish girl's search for refuge resembles the state of Polish society. The appearance of Mirka results in confusion, and later, trouble. This was already signalled by Rozewicz in an exceptional scene from "Letter from the Camp" in which the boy's neighbour, seeing a fugitive Russian soldier, retreats immediately, admitting that "Now, people worry only about themselves." Such embarassing excuses mask fear. During the occupation, no one feels safe. Neither social status not the aegis of a charity organisation protects against repression. We see the potential guardians of Mirka passing her back and forth among themselves. These are friendly hands but they cannot offer strong support. The story takes place on that thin line between solidarity and heroism. Solidarity arises spontaneously, but only some are capable of heroism. Help for the girl does not always result from compassion; sometimes it is based on past relations and personal ties (a neighbour of the doctor takes in the fugitive for a few days because of past friendship). Rozewicz portrays all of this in a subtle way; even the smallest gesture has significance. Take, for example, the conversation with a stranger on the train: short, as if jotted down on the margin, but so full of tension. And earlier, a peculiar examination of Polishness: the "Holy Father" prayer forced on Mirka by the village boys to check that she is not a Jew. Would not rising to the challenge mean a death sentance?

Viewed after many years, "Birth Certificate" discloses yet another quality that is not present in the works of the Polish School, but is prominent in later B-class war films. This is the picture of everyday life during the war and occupation outlined in the three novellas. It harmonises with the logic of speaking about "life after life". Small heroes of Rozewicz suddenly enter the reality of war, with no experience or scale with which to compare it. For them, the present is a natural extension of and at the same time a complete negation of the past. Consider the sleey small-town marketplace, through which armoured columns will shortly pass. Or meet the German motorcyclists, who look like aliens from outer space - a picture taken from an autopsy because this is how Stanislaw and Taduesz perceived the first Germans they ever met. Note the blurred silhouettes of people against a white wall who are being shot - at first they are shocking, but soon they will probably become a part of the grim landscape. In the city centre stands a prisoner camp on a sodden bog ("People perish likes flies; the bodies are transported during the night"); in the street the childern are running after a coal wagon to collect some precious pieces of fuel. There's a bustle around some food (a boy reproaches his younger brother's actions by singing: "The warrant officer's son is begging in front of the church? I'm going to tell mother!"); and the kitchen, which one evening becomes the proscenium of a real drama. And there are the symbols: a bar of chocolate forced upon a boy by a Wehrmacht soldier ("On the Road"); a pair of shoes belonging to Zbyszek's father which the boy spontaneously gives to a Russian fugitive; a priceless slice of bread, ground under the heel of a policeman in the guter ("Letters from the Camp"). As the director put it: "In every film, I communicate my own vision of the world and of the people. Only then the style follows, the defined way of experiencing things." In Birth Certificate, he adds, his approach was driven by the subject: "I attempted to create not only the texture of the document but also to add some poetic element. I know it is risky but as for the merger of documentation and poety, often hidden very deep, if only it manages to make its way onto the screen, it results in what can referred to as 'art'."

After 1945, there were numerous films created in Europe that dealt with war and children, including "Somewhere in Europe" ("Valahol Europaban", 1947 by Geza Radvanyi), "Shoeshine" ("Sciescia", 1946 by Vittorio de Sica), and "Childhood of Ivan" ("Iwanowo dietstwo" by Andriej Tarkowski). Yet there were fewer than one would expect. Pursuing a subject so imbued with sentimentalism requires stylistic disipline and a special ability to manage child actors. The author of "Birth Certificate" mastered both - and it was not by chance. Stanislaw Rozewicz was always the beneficent spirit of the film milieu; he could unite people around a common goal. He emanated peace and sensitivity, which flowed to his co-workers and pupils. A film, being a group work, necessitates some form of empathy - tuning in with others.

In a biographical documentary about Stanislaw Rozewicz entitled "Walking, Meeting" (1999 by Antoni Krauze), there is a beautiful scene when the director, after a few decades, meets Beata Barszczewska, who plays Mireczka in the novella "Drops of Blood". The woman falls into the arms of the elderly man. They are both moved. He wonders how many years have passed. She answers: "A few years. Not too many." And Rozewicz, with his characteristic smile says: "It is true. We spent this entire time together."

天狗党

1864年(元治元年),德川幕府岌岌可危,国内各藩蠢蠢欲动,国外列强叩响国门。是年,水戸藩士藤田小四郎等下级武士以“尊王攘夷”为口号,组建天狗党,在筑波山起兵。一时间,保守派和激进派纷争不断,狼烟四起,整个国家陷入动荡之中。

底层农民真壁仙太郎(仲代达矢 饰)因拖欠地租被地主鞭笞,为路过的天狗党头目新五左卫门救下。备受感动的仙太郎决心加入天狗党,革新时弊,扫除压迫。然而一次次的行动,让他对天狗党的作为和宗旨渐渐产生怀疑……

红星照耀中国2019

《红星照耀中国》电影剧组创作灵感及素材就取自同名报告文学——美国记者斯诺根据自身经历创作的《红星照耀中国》一书。影片主要讲述的是1936年美国青年埃德加·斯诺冒险来到中国红色革命区域的的亲历见闻,在采访和见证了毛泽东、周恩来等共产党领导人,以及红军战士和苏区百姓的风采之后,斯诺以饱含激情的生动文笔写成了《红星照耀中国》一书,该书出版后轰动世界,使全球第一次了解到了彼时艰苦抗战背景下中国共产党的真实情况。

打过长江去

《打过长江去》以渡江战役为背景,再现了新中国成立前的关键时刻,人民解放军一支先遣分队潜入江南,打进虎穴斗智斗勇,命悬一线却与各种敌人殊死斗争,为祖国统一而舍生取义、无私拼搏, 最终配合百万大军过长江,将红旗插遍中国。

小戏骨:洪湖赤卫队

小戏骨《洪湖赤卫队》是以王玉珍主演的《洪湖赤卫队》为蓝本改编,讲述1930年湖北沔阳县委为配合红军行动,暂时把赤卫队撤离彭家墩。彭家墩恶霸彭霸天趁红军转移暂离洪湖之际卷土重来。洪湖赤卫队在乡党支部书记韩英和队长刘闯的带领下,与敌人展开了艰苦曲折的斗争。韩英不幸被捕入狱。面对敌人的威逼利诱,韩英始终坚贞不屈。赤卫队最终打回彭家墩,消灭了保安团和地方反动武装,红旗又在洪湖上迎风飘扬。

解放·终局营救

1949年1月,中国人民解放军将国民党 50 万军队围困于平津地区,总攻在即。是否能和平解放北平,取决于天津一战。此时的天津城内,暗堡、工事林立,士兵荷枪实弹进入状态,大战前的天津城已是一座炼狱。为了总攻的发动扫平道路,解放军炮兵侦察连连长蔡兴福、侦察兵马宝树、报务员廖枫、炮兵见习参谋葛贵忱四人临危受命,组成解放炮兵侦察别动队,乔装潜入天津城。此时,负责转移北平守军眷属的国军军需官姚哲在宪兵营长钱卓群的暗算下成为通缉犯,带女儿出逃时恰好与进城的蔡兴福一行人相遇,蔡兴福挟持姚哲欲完成任务。随着目标任务的逐步明晰,姚哲被暗算背后的秘密、钱卓群企图破坏北平和谈的阴谋、蔡兴福失踪儿子的下落都渐渐浮现出来……

八子

上世纪30年代的赣南地区,在这个被称为中国革命“红色摇篮”的地方,曾经有这样一位母亲,她将八个儿子先后送入红军,奔赴战场前线。但战火无情,兄弟中的六人陆续牺牲,只剩下大哥杨大牛和最小的孩子满崽。满崽找到了大牛的部队,成了哥哥麾下的普通一兵,一场场艰苦战役的淬炼让新兵满崽迅速成长为一个真正的战士。最后的战斗打响了,为了掩护大部队安全撤离,杨大牛带领弟弟满崽和全体战友浴血肉搏,直至弹尽粮绝……

英雄的身前,是枪林弹雨的沙场,而在英雄的身后,家乡的村庄依然宁静安详,微风吹过金黄的稻浪簌簌作响,一位年迈的母亲正在村头的小路旁孤独的守望……

影片根据江西赣南地区家喻户晓的“八子参军”的故事改编。在战火硝烟的年代,千万人民群众投入到支援革命战争中,奉献了自己的一切。作为那个残酷年代的缩影,骨肉相连的母子情、不离不弃的兄弟情、赤胆忠心的家国情.....无数荡气回肠、难以割舍的情感凝聚于影片之中,共同谱写了一首可歌可泣、永垂不朽的英雄乐章。

法尔什家族

夜幕降临,一架四引擎飞机在机场着陆,走下飞机的是唯一的乘客乔•法尔什——作为法尔什犹太家族最后的幸存者,自从他1938年离开柏林,至今已有四十个年头。在机场到达大厅里等待着乔的,是包括父母、姐妹、兄弟等在集中营丧命的死去的家族以及乔之前所深爱、最终在柏林的轰炸中丧命的纳粹分子的女儿莉莉。一场跨越生死世界的庆典与邂逅就此展开。本片是比利时著名导演组合达内兄弟的剧情片处女作。(小易甫字幕组)

长岛

噩运降临之前,

李丰独自出门。

儿子和丈夫不懂,

她只是想一个人走走。

生活在一座岛上,

陆地的终点并不遥远。

夜之钻

杨·南曼奇在捷克新浪潮的地位,类似于雷奈在法国新浪潮一样。这是他的第一部剧情长片,描绘两个犹太男孩在被送往死亡集中营的途中,从火车上逃脱,被迫在乡野展开挣扎,艰难地求生存的故事,看似具备写实的基础,却被混合了幻想的影像,以及自由跳跃的叙事所重组。

中国蓝盔

我国首部维和军事题材电影《中国蓝盔》讲述了当下中国维和部队官兵在非洲坚决执行习主席指示的“构建人类命运共同体”的大国方针、严格履行联合国赋予的使命,派出了以“兵王”杜峰为首的作战小组冒着生命危险,从恐怖分子手中救出联合国调查组,从而阻止了一场一触即发的战争,维护了难民营的生活秩序、保障了难民们的生活权益。但是年轻的战士也在这次行动中为了维护非洲的和平而献出了宝贵的生命……

无问西东

如果提前了解了你所要面对的人生,你是否还会有勇气前来?吴岭澜、沈光耀、王敏佳、陈鹏、张果果,几个年轻人满怀诸多渴望,在四个非同凡响的时空中一路前行。

吴岭澜(陈楚生 饰),出发时意气风发,却很快在途中迷失了方向。沈光耀(王力宏 饰),自愿参与了最残酷的战争,他一直在努力去做那些令他害怕,但重要的事。王敏佳(章子怡 饰)最初的错误,只是为了虚荣撒了一个小谎;最初的烦恼,只是在两个优秀的男人中选择一个。但命运,却把她拖入被众人唾骂的深渊。陈鹏(黄晓明 饰)把爱情摆在了理想前面,但爱情却没有把他摆在前面。他说,“我有人要照顾”,纵然这意味着与所有人作对,意味着要和她一起被放逐千里。张果果(张震 饰),身处尔虞我诈的职场,“赢”是他的习惯。为了赢,他总是见招拆招,先发制人。而有一天,他却面临了一个比“赢”更重要的选择。这几个年轻人,在最好的年纪迎来了最残酷的考验,并成就了永不褪色的青春传奇。

出生证明

In 1961, Stanislaw Rozewicz created the novella film "Birth Certificate" in cooperation with his brother, Taduesz Rozewicz as screenwriter. Such brother tandems are rare in the history of film but aside from family ties, Stanislaw (born in 1924) and Taduesz (born in 1921) were mutually bound by their love for the cinema. They were born and grew up in Radomsk, a small town which had "its madmen and its saints" and most importanly, the "Kinema" cinema, as Stanislaw recalls: for him cinema is "heaven, the whole world, enchantment". Tadeusz says he considers cinema both a charming market stall and a mysterious temple. "All this savage land has always attracted and fascinated me," he says. "I am devoured by cinema and I devour cinema; I'm a cinema eater." But Taduesz Rozewicz, an eminent writer, admits this unique form of cooperation was a problem to him: "It is the presence of the other person not only in the process of writing, but at its very core, which is inserperable for me from absolute solitude." Some scenes the brothers wrote together; others were created by the writer himself, following discussions with the director. But from the perspective of time, it is "Birth Certificate", rather than "Echo" or "The Wicked Gate", that Taduesz describes as his most intimate film. This is understandable. The tradgey from September 1939 in Poland was for the Rozewicz brothers their personal "birth certificate". When working on the film, the director said "This time it is all about shaking off, getting rid of the psychological burden which the war was for all of us. ... Cooperation with my brother was in this case easier, as we share many war memories. We wanted to show to adult viewers a picture of war as seen by a child. ... In reality, it is the adults who created the real world of massacres. Children beheld the horrors coming back to life, exhumed from underneath the ground, overwhelming the earth."

The principle of composition of "Birth Certificate" is not obvious. When watching a novella film, we tend to think in terms of traditional theatre. We expect that a miniature story will finish with a sharp point; the three film novellas in Rozewicz's work lack this feature. We do not know what will be happen to the boy making his alone through the forest towards the end of "On the Road". We do not know whether in "Letter from the Camp", the help offered by the small heroes to a Soviet prisoner will rescue him from the unknown fate of his compatriots. The fate of the Jewish girl from "Drop of Blood" is also unclear. Will she keep her new impersonation as "Marysia Malinowska"? Or will the Nazis make her into a representative of the "Nordic race"? Those questions were asked by the director for a reason. He preceived war as chaos and perdition, and not as linear history that could be reflected in a plot. Although "Birth Certificate" is saturated with moral content, it does not aim to be a morality play. But with the immense pressure of reality, no varient of fate should be excluded. This approached can be compared wth Krzysztof Kieslowski's "Blind Chance" 25 years later, which pictured dramatic choices of a different era.

The film novella "On the Road" has a very sparing plot, but it drew special attention of the reviewers. The ominating overtone of the war films created by the Polish Film School at that time should be kept in mind. Mainly owing to Wajda, those films dealt with romantic heritage. They were permeated with pathos, bitterness, and irony. Rozewicz is an extraordinary artist. When narrating a story about a boy lost in a war zone, carrying some documents from the regiment office as if they were a treasure, the narrator in "On the Road" discovers rough prose where one should find poetry. And suddenly, the irrational touches this rather tame world. The boy, who until that moment resembled a Polish version of the Good Soldier Schweik, sets off, like Don Quixote, for his first and last battle. A critic described it as "an absurd gesture and someone else could surely use it to criticise the Polish style of dying. ... But the Rozewicz brothers do no accuse: they only compose an elegy for the picturesque peasant-soldier, probably the most important veteran of the Polish war of 1939-1945." "Birth Certificate" is not a lofty statement about national imponderabilia. The film reveals a plebeian perspective which Aleksander Jackieqicz once contrasted with those "lyrical lamentations" inherent in the Kordian tradition. However, a historical overview of Rozewicz's work shows that the distinctive style does not signify a fundamental difference in illustrating the Polish September. Just as the memorable scene from Wajda's "Lotna" was in fact an expression of desperation and distress, the same emotions permeate the final scene of "Birth Certificate". These are not ideological concepts, though once described as such and fervently debated, but rather psychological creations. In this specific case, observes Witold Zalewski, it is not about manifesting knightly pride, but about a gesture of a simple man who does not agree to be enslaved.

The novella "Drop of Blood" is, with Aleksander Ford's "Border Street", one of the first narrations of the fate of the Polish Jews during the Nazi occupation. The story about a girl literally looking for her place on earth has a dramatic dimension. Especially in the age of today's journalistic disputes, often manipulative, lacking in empathy and imbued with bad will, Rozewicz's story from the past shocks with its authenticity. The small herione of the story is the only one who survives a German raid on her family home. Physical survial does not, however, mean a return to normality. Her frightened departure from the rubbish dump that was her hideout lead her to a ruined apartment. Her walk around it is painful because still fresh signs of life are mixed with evidence of annihilation. Help is needed, but Mirka does not know anyone in the outside world. Her subsequent attempts express the state of the fugitive's spirits - from hope and faith, moving to doubt, a sense of oppression, and thickening fear, and finally to despair.

At the same time, the Jewish girl's search for refuge resembles the state of Polish society. The appearance of Mirka results in confusion, and later, trouble. This was already signalled by Rozewicz in an exceptional scene from "Letter from the Camp" in which the boy's neighbour, seeing a fugitive Russian soldier, retreats immediately, admitting that "Now, people worry only about themselves." Such embarassing excuses mask fear. During the occupation, no one feels safe. Neither social status not the aegis of a charity organisation protects against repression. We see the potential guardians of Mirka passing her back and forth among themselves. These are friendly hands but they cannot offer strong support. The story takes place on that thin line between solidarity and heroism. Solidarity arises spontaneously, but only some are capable of heroism. Help for the girl does not always result from compassion; sometimes it is based on past relations and personal ties (a neighbour of the doctor takes in the fugitive for a few days because of past friendship). Rozewicz portrays all of this in a subtle way; even the smallest gesture has significance. Take, for example, the conversation with a stranger on the train: short, as if jotted down on the margin, but so full of tension. And earlier, a peculiar examination of Polishness: the "Holy Father" prayer forced on Mirka by the village boys to check that she is not a Jew. Would not rising to the challenge mean a death sentance?

Viewed after many years, "Birth Certificate" discloses yet another quality that is not present in the works of the Polish School, but is prominent in later B-class war films. This is the picture of everyday life during the war and occupation outlined in the three novellas. It harmonises with the logic of speaking about "life after life". Small heroes of Rozewicz suddenly enter the reality of war, with no experience or scale with which to compare it. For them, the present is a natural extension of and at the same time a complete negation of the past. Consider the sleey small-town marketplace, through which armoured columns will shortly pass. Or meet the German motorcyclists, who look like aliens from outer space - a picture taken from an autopsy because this is how Stanislaw and Taduesz perceived the first Germans they ever met. Note the blurred silhouettes of people against a white wall who are being shot - at first they are shocking, but soon they will probably become a part of the grim landscape. In the city centre stands a prisoner camp on a sodden bog ("People perish likes flies; the bodies are transported during the night"); in the street the childern are running after a coal wagon to collect some precious pieces of fuel. There's a bustle around some food (a boy reproaches his younger brother's actions by singing: "The warrant officer's son is begging in front of the church? I'm going to tell mother!"); and the kitchen, which one evening becomes the proscenium of a real drama. And there are the symbols: a bar of chocolate forced upon a boy by a Wehrmacht soldier ("On the Road"); a pair of shoes belonging to Zbyszek's father which the boy spontaneously gives to a Russian fugitive; a priceless slice of bread, ground under the heel of a policeman in the guter ("Letters from the Camp"). As the director put it: "In every film, I communicate my own vision of the world and of the people. Only then the style follows, the defined way of experiencing things." In Birth Certificate, he adds, his approach was driven by the subject: "I attempted to create not only the texture of the document but also to add some poetic element. I know it is risky but as for the merger of documentation and poety, often hidden very deep, if only it manages to make its way onto the screen, it results in what can referred to as 'art'."

After 1945, there were numerous films created in Europe that dealt with war and children, including "Somewhere in Europe" ("Valahol Europaban", 1947 by Geza Radvanyi), "Shoeshine" ("Sciescia", 1946 by Vittorio de Sica), and "Childhood of Ivan" ("Iwanowo dietstwo" by Andriej Tarkowski). Yet there were fewer than one would expect. Pursuing a subject so imbued with sentimentalism requires stylistic disipline and a special ability to manage child actors. The author of "Birth Certificate" mastered both - and it was not by chance. Stanislaw Rozewicz was always the beneficent spirit of the film milieu; he could unite people around a common goal. He emanated peace and sensitivity, which flowed to his co-workers and pupils. A film, being a group work, necessitates some form of empathy - tuning in with others.

In a biographical documentary about Stanislaw Rozewicz entitled "Walking, Meeting" (1999 by Antoni Krauze), there is a beautiful scene when the director, after a few decades, meets Beata Barszczewska, who plays Mireczka in the novella "Drops of Blood". The woman falls into the arms of the elderly man. They are both moved. He wonders how many years have passed. She answers: "A few years. Not too many." And Rozewicz, with his characteristic smile says: "It is true. We spent this entire time together."

本站内容均从互联网收集而来,仅供交流学习使用,版权归原创者所有如有侵犯了您的权益,尽请通知我们,本站将及时删除侵权内容。